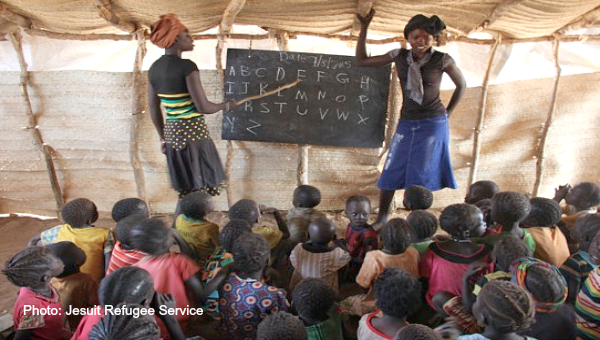

In South Sudan’s Upper Nile state, a student is more likely to find soldiers occupying their school than teachers preparing lessons. Sixty-three percent of schools are occupied by armed forces. Even more of a rare commodity than functioning school buildings are teachers themselves.

“The government is basically not present here… they are devoting most of the resources into warfare so they are interested in defense, in military and therefore education, social services, health are very minimal,” said Fr Pau Vidal SJ, Jesuit Refugee Service, Maban project director.

Since the renewal of conflict in December 2013, the South Sudanese government has stopped nearly all educational funding leaving teachers without the basic salaries necessary to survive, especially in remote areas like Upper Nile.

Regardless, the desire to learn in both refugee and local communities in Maban County, Upper Nile, is strong. While some teachers have left the profession to take on new jobs which pay a proper salary, others have remained to teach as volunteers.

“Our biggest challenge is the number of children. Sometimes one teacher will have 200 children in a class, making it difficult for them to follow the lesson. Many fall behind, getting lost in the classroom,” said Mustafa, a refugee teacher.

Teachers like Mustafa are taking matters into their own hands to ensure a younger generation of Sudanese and South Sudanese do not miss out on an education.

“Education is vital, during this time when many live amidst violence… Back home there are children of 13, 14, 15 years holding guns. They’ve never had education and that’s why they become soldiers. So in this (refugee) camp we want to teach these children so they have a different way of life. We know they’ll bring peace to our home,” said Sali, a refugee from Blue Nile, Sudan and teacher in one of the four refugee camps in Maban County.

Building capacity of teachers.

After living through years of conflict and displacement, most of the teachers, both from refugee and host communities, have not had the opportunity to finish secondary school or even primary school. Those who did previously studied only in Arabic. When the official language of South Sudan became English many students and teachers had to switch gears, facing classes in a language they never learned.

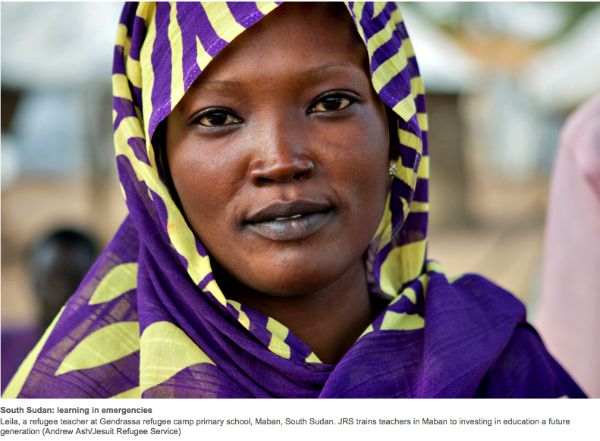

“In Blue Nile everything was in Arabic but I know that here I need to learn English. Once you learn English you have higher opportunities. You’re better equipped later in life,” said Leila, another refugee teacher.

In an effort to support these teachers, JRS began a teacher training programme in 2014. There are more than 100 primary school teachers from both the local Mabanese and refugee communities in the programme. The training offers courses in English and teaching methodology as well as science, math and social studies.

“I don’t think I could imagine a JRS intervention in Maban without doing teacher training. We are in a country where more than 65, nearly 70, percent of the population is illiterate… Teachers are alone, they don’t have the support of the government…We have to support them, to empower them and this is the hope of education in Maban,” said Alvar Sanchez SJ, JRS Maban education coordinator.

“To become more we need to learn more…to continue to grow. We are already teachers but we are training to become quality teachers,” said Mangistu from South Sudan, a student in the host community training.

Emerging role models.

Teachers are key in making sure girls attend and remain in school. Educated women, especially teachers, are regarded by community members as role models. In an area where a girl is more likely to die in childbirth than finish primary school, such role models can be lifesavers.

Families often rely on the dowries they receive from marrying off their daughters – sometimes as young as 14 years old – to survive. Teachers are some of the only advocates for young girls who wish to finish their schooling.

“When people see me walking on the road [to school] they laugh at me, but I know I need to learn so I go anyway. Let girls come to school like me. If you are not educated then in the future you get nothing,” said Elizabeth, a teacher in the host community.

“If a girl goes to school, she’ll send her own daughters to school. Then they’ll say ‘my mother is educated and she leads the community. I want to be like her’,” said Miriam, a Sudanese refugee teacher.

In the years to come, JRS hopes that an intervention focusing on teachers, those who foster the future of their countries, will result in students equipped to lead their communities.

“Very often donors and even humanitarian agencies would argue that the first thing (in an emergency) is to provide food, shelter, healthcare – which is true – however life is not only about a body to be fed, a body to be sheltered. Life is also about meaning, learning and preparing for a future that might not be very immediate but eventually will happen,” said Pau.

Author: Angela Wells, JRS Eastern Africa Communications Officer, 10th August 2015