On International Women’s Day, we hear from women who are living on Doro, Batil and Kaya Refugee Camps in Maban, South Sudan about their struggles and hopes. They are refugees from Sudan’s Blue Nile state, or internally displaced from South Sudan. The women are all students and graduates of the Jesuit Refugee Service(JRS) Teacher Training Unit.

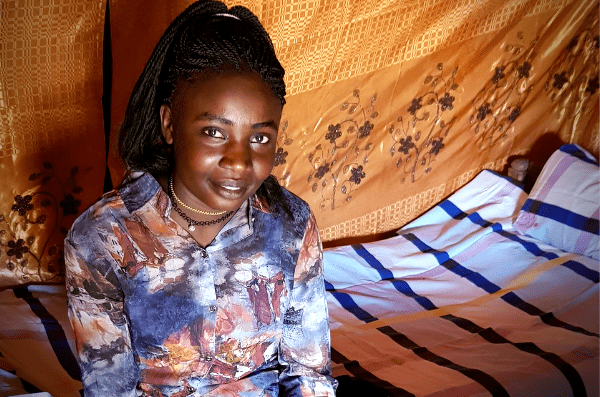

Basamat Alnoor Jakolo is a 22-year-old woman who lives on the Kaya Refugee camp with her father, mother and extended family. They have been refugees in Maban since fleeing the Blue Nile region in 2011. She is a graduate of the JRS teacher training programme and is now employed as a teacher in the camp.

She began teaching children informally on the refugee camp when she was just 14, teaching them local songs, games and other activities, and has been employed as a qualified teacher since graduating from the JRS teacher training college. She takes pride in her position, saying “Now that I am a teacher, I am respected by everybody in the community. I hope one day to further my education and do more study”

Basamat’s father recognised his daughter’s abilities and encouraged her to be educated, which is unusual for her tribe, the Angassana. She has six siblings but is the only one who has received an education. He now runs a small clothes shop in the camp and is very proud of his daughter, who is able to share her monthly income from teaching with him and her extended family there.

Life is difficult for residents of the camp, who struggle to get water. Basamat says “In Kaya Refugee Camp people are facing many problems around access to water. We used to have water for two hours a day – now with the shortages woman are buying it in the market. The women here sometimes have to walk for over an hour with two jerrycans to get water”.

Despite the hardships of Kaya Refugee Camp, Basamat does not think it will be possible to return home to Sudan.

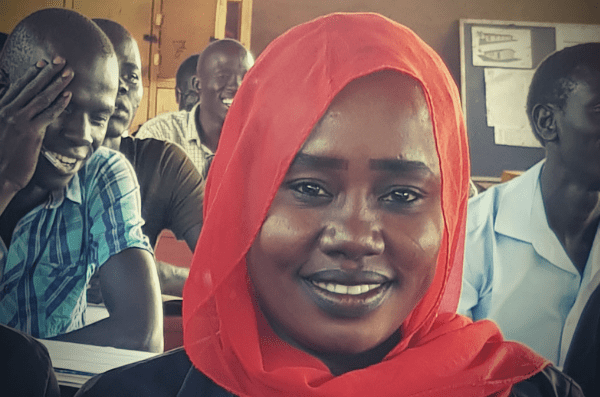

45-year-old Gizma fled her village in the Blue Nile state of Sudan with her husband and three children, and their extended family. They walked for three months to reach Maban after walking for three months. She learned English in her new home, Batil Refugee Camp.

Gizma wants her daughter to have a better life than she has had, and believes that education is the path to success, and says “I want my daughter and my two boys to go to school because education is more important than anything else. When my daughter is educated, she can help me now and as an old woman and she can also help herself in the future” She learned English in Batil Refugee Camp, something she credits with giving her a ticket to a new life and brighter future.

She recalls that “When we were living in Sudan, we didn’t know our rights, our rights to education, to health, whatever. Now things have changed and education for girls has increased, it’s not like before. In the camp girls are going to primary school and some are going to secondary school. I think it’s important that girls are aware of the importance of getting an education.”

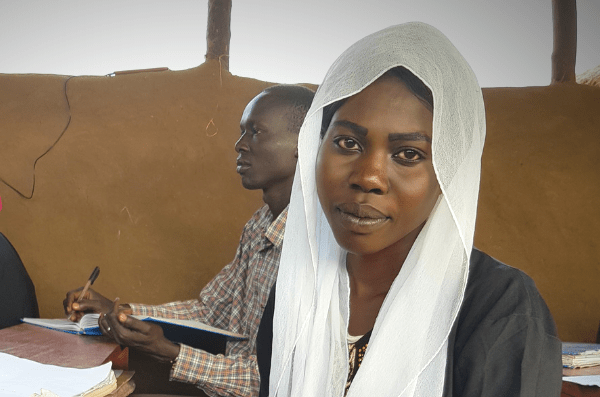

“If I become a teacher, my children will have a better future and they will be good and healthy. My parents will also have a better life” says softly-spoken Hawa Juma, who is 21 and married with one child.

She is currently completing her teacher training certificate and would like to go on an achieve a diploma in the future. Hawa is supporting her parents, sister and extended family who are all living in Batil Refugee Camp. She would love to return to her home in Sudan, but does not think she will ever be able to do that.

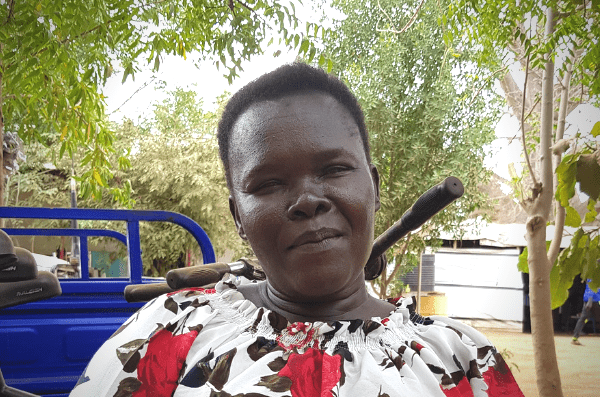

Flora Kiden Justin is an IDP (internally displaced person) from her home in Yei, South Sudan. She and her two children left six years ago because of the ongoing violence there, and she doubts they will return.

She teaches Arabic women in the camp to speak English, and tells them “that education is the key to success. I tell my female students that when you educate a girl you educate a family and an entire country“.

Flora is opposed to the country’s culture of early marriage. “Most of the girls in South Sudan are getting married as soon as they reach puberty – so from 14, 15 and 16 years of age and then once they get married – their education stops. You see the more children a woman has the more respect she gets in her community and village – so there is no chance for a women to get rest or get an education as they believe their role is to produce more children.”

With thanks to Susan Cahill.