Maban is in the north-east of South Sudan and is one of the most isolated and marginalised regions in the world. This dusty expanse is home to over 160,000 refugees living across four UNHCR refugee camps, Doro, Batil, Kaya and Gendrassa. Women and children making up most of the refugee population.

Resilience in South Sudan

When Gizma, a 45-year-old mother of 3 children arrived in Maban she had left her whole life behind, her family, her friends and everyone she knew. “We came to South Sudan because South Sudan is safe – there is no war here.”

“I walked with my mother, my husband and children for over 3 months. It was very difficult,” she said.

“I am one of the lucky ones,” she added.

Doro Camp was the first refugee camp to open in Maban County in 2011 and it is the most overcrowded. According to the UNHCR most of the population “are highly reliant on food aid.”

My first impressions of Doro was dominated by the vast expanse of the camp, it took over two hours to walk across and the enormous scale of the humanitarian needs. All you can see for miles and miles are sprawling bamboo shacks and mud huts and hundreds of children playing amongst dirt and sand.

Most of the refugees on Doro come from the Uduk and the Ingessana tribes from the Blue Nile region of Sudan. In Doro Camp, there are only 7 schools for a population of over 50,000 people. 60 percent of its adult population are unemployed.

“In Sudan our daily life was very good. In Sudan you could wake up every morning and feel free because it’s your country,” says Basamat, a bright and chatty Blue Nile refugee.

“When you are in your country you feel comfortable,” she said.

Basamat fled Sudan in 2011 with her mother and five sisters. She walked for several months before she reached Maban.

She said “My father does not like girls – he said you girls are useless, I need a boy, I said father don’t worry I will do what boys do, he tells me no. So, I told my mother, don’t worry, I will get educated and do what boys are doing in the future.”

This month, Basamat is graduating with a Certificate in Education with the support of JRS in Maban.

“The JRS have given us great hope and I am thankful to JRS and to all the donors who support them.”

The Humanitarian Crisis in South Sudan

South Sudan is the world’s youngest nation and is home to Africa’s largest refugee and humanitarian crisis.

The World Food Programme estimates that 7.5 million of South Sudan’s population are in need humanitarian assistance while it is estimated that over 860,000 of children under the age of five are acutely malnourished.

This month the World Food Programme is operating with 75 percent of the funds that it needs to support its operations in South Sudan.

The Jesuit Refugee Service in South Sudan

Education and literacy is a major challenge in South Sudan. In Maban this problem is intensified due to the regions remote and isolated location. According to UNHCR half of the population have received no education with more female’s illiterate than males.

Since 2011, the Jesuit Refugee Service has been working in Maban providing much needed humanitarian support and services to host and refugee communities. The idea of accompaniment is central to their work.

I spent a week on Doro, the largest of the refugee camps in Maban where the JRS runs a variety of humanitarian programmes – a day care centre for disabled children, a counselling and psychosocial support clinic for women and youths and a range of home visit programmes for the disabled and the elderly.

In addition, the JRS operates an impressive education centre close to the town of Bunj, providing training for refugee teachers. This centre is providing a glimmer of hope for the future generations.

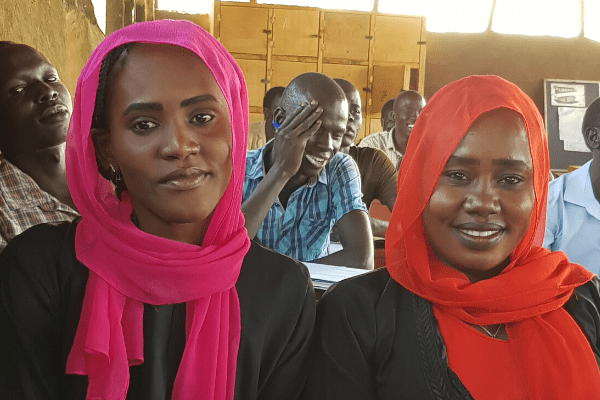

Students at the JRS Education Unit, Maban, South Sudan

“When you educate a girl, you educate a family and an entire country,” says Flora a 49-year-old mother from the Equatoria region of South Sudan.

Before the war Flora had a good job and was sending her daughters to a private school. Flora’s parents and siblings lived close by. But like thousands of other South Sudanese the conflict turned her life upside down. In 2014, Flora fled her village on the outskirts of Yei. Today Flora teaches English skills to refugee women.

Flora tells me the women of South Sudan have only one choice – “to look forward, not back.”

“I am a strong lady and I do not bury myself in my challenges because this is our country and it is us – the people of South Sudan who will improve our country in the future,” she said.

Flora has two sisters living on a refugee camp in Uganda and one brother living in Juba, the capital of South Sudan and another brother living in the UK.

“It’s not possible for me to return home,” she added. Flora’s story is not unusual.

South Sudan Refugee Crisis

According to UNHCR over 2.3 million people have fled the conflict in South Sudan and are living on refugee camps mainly in Ethiopia, Sudan and Uganda, while inside the country approximately 1.47 million people have been forced from their homes and are internally displaced.

Today there are over 4.3 million refugees, IDPs and asylum seekers living in South Sudan, 92% coming from the Blue Nile region of Sudan.

This month thirty refugees from Maban will graduate with a Certificate in Teacher Training. Six of these students are mothers, daughters and sisters – blazing a trail for other refugee women.

“I am very proud of myself and I am very grateful to JRS for this chance I got,” says Hawa Juma, a soft-spoken 21-year-old Blue Nile refugee.

Hawa fled Sudan in 2011 and lives on Batil refugee camp with her husband, mother and older sister. Hawa tells me she is determined “to improve her skills” and her situation.

“If I become a teacher, my children will have a better future. My parents will also have a better life,” she added.

Tackling Gender Equality Through Education

Batil is the second largest camp in Maban and it is a worryingly unstable and precarious place. With a population of 40,221 the camp is currently facing many sanitation challenges due to lack of land and the increasing number of refugee arrivals.

About half the population is under 18 years of age and violence against women and girls is a serious problem. Child marriage and inter communal violence is commonplace.

“The biggest challenge on Batil is security,” says Elizabeth a 25 year old Blue Nile refugee. “A few months ago there were raids on the camp,” she says. “We need more security on the camp,” she added.

“When we were living in Sudan, we didn’t know our rights, our rights to education and are rights to health” says Gizma.

“Now things have changed and education for girls has increased, it’s not like before. In the camp girls are going to primary school – some are going to secondary school,” she added.

I asked Gizma, What are her hopes for the future?

“I want my daughter and my two boys to go to school because education is more important than anything else,” she said.

JRS Accompaniment

“There is something remarkable about the people here in Maban,” says Fr. Tony O’Riordan SJ, the Project Director of the JRS in Maban.

“The refugees here find themselves stuck between two conflicts – the conflicts at home and the conflict in South Sudan.”

O’Riordan began his ministry in South Sudan just under two years ago having served as the parish priest of Moyross in Limerick for over six years.

“The refugees live in abject poverty, but they live in a spiritual richness. There is a genuine sense of joy, a genuine sense of appreciation and of mental wellbeing in the midst of this situation because they are in it together. They have a sense of belonging and community and they share the challenges together.”

“The people here are wise, they don’t want the model of development that we have pursued,” he added.

JRS Psychosocial Unit on Doro Refugee Camp

Resilience is redefined every day on Doro refugee camp.

Winnie Nandwa works as an occupational therapist with the Jesuit Refugee Service on Doro. “People come to the clinic for many reasons. They have a lot of questions,” she says.

“The mothers here have so many challenges especially when it comes to poverty and the loss of their husbands and family members. It takes a lot of time for them to adjust. They have this child who is living with a disability and they may not have any family supports.”

“In a week we can see 75 to 100 children living with disabilities. Some of the mothers are desperate, they have so many needs and they are very poor and it’s very expensive for them to maintain a child with a disability.

“Added to this some of the mothers may have experienced sexual violence on their journey to the refugee camp.”

Occupational Therapy Room, JRS Psychosocial Centre, Doro Refugee Camp, Maban, South Sudan

“You may get a child who is two years old and is not able to walk or to sit down.

“We train them to walk, to talk, to dress themselves and to be as independent as possible.”

“I really don’t want to imagine what would happen if the JRS was not here,” she added.

“Since the JRS has come to Maban, they have done a lot,” says Miriam a 38-year-old Mabanese mother of 5 children. I met Miriam on her dusty compound close to Bunj town, the capital of Maban. Miriam works as a Psychosocial Home Visitor with the JRS and believes “education is the key to changing attitudes.”

“Refugees have become very close with the community. When the peace comes maybe some of them will stay,” she added.

Miriam sitting with her son on her compound in Bunj, Maban, South Sudan

Surviving Daily Life on Kaya Refugee Camp

Kaya Camp is the newest refugee camp in Maban and is home to over 21,902 refugees. Most of the refugees on Kaya do not have enough to eat and access to drinking water is limited. Unemployment and limited training opportunism are the biggest challenges facing its youth.

While there is a small market on Kaya, most of its young people have no source of income. This has led to widespread boredom, distress and depression.

Currently, most children in Kaya have to travel to Doro or Batil to attend secondary school.

“On Kaya Refugee Camp people are facing many problems around access to water,” says Basamat Alnoor Jakolo, a 22-year old Blue Nile Refugee from the Angassana Tribe. Basamat is tall, proud and very confident. She has big dreams for the future.

Basamat Alnoor Jakolo at the water pump on Kaya Refugee Camp, Maban, Camp South Sudan

In 2011, Basamat fled her village in Sudan with her parents, six brothers and sisters and extended family. Basamat was just 14 years old.

“We had to walk for over three months. It was very difficult,” she said.

“There was no education on the camp or anything to do so I started teachings some of the children some songs and games,” she said.

“The problem here on Kaya is shortage of water. We have no water. We used to have water for 2 hours a day, but now with the water shortages woman are buying water in the market. The women here on Kaya sometimes have to walk for over an hour with two jerry cans to get water,” she added.

“I am the only one in my family to go to my school. Some of my brothers went to school but they dropped out.”

In 2018, Basamat completed a Certificate in Education with the Jesuit Refugee Service in Maban and today is gaining some degree of independence. Like many refugees with a small income – Basamat supports her family and her uncle.

“Now that I am a teacher, I am respected by everybody in this community. I hope one day to further my education and do more study,” she said.

Hope for the Future

It’s difficult to describe Maban. On any day there can be great highs and great lows, everyday miracles mixed with huge suffering and pain. The scale of the needs can be overwhelming. However, there is one constant in it all – the creativity, dignity and absolute resilience of the people.

“I’m optimistic,” says Fr O’Riordan, “because the people here are optimistic and they are very resilient and bright, they have struggled for decades here.”

“The most essential step is peace in both countries. We must continue to work for peace and justice,” he added.

Susan Cahill’s visit to South Sudan was supported by Irish Jesuit Missions.

(Main photo: Basamat Osman Atom and Gizma Abdalkrim Daldum, JRS Teaching Unit.)