There are 122 confirmed cases of coronavirus in Uganda so far, with no deaths [as of 12 May]. But the pandemic has exacerbated the challenges posed by heavy rains in East Africa this year and the threat from swarms of locusts. The economy is under severe pressure and key sectors like tourism, transport, construction, manufacturing and agriculture are at risk.

The Covid-19 lockdown, now in place for more than six weeks, has been strict – everything except food shops and pharmacies closed, a night curfew was imposed and no public and private transportation was permitted. Churches, mosques and temples shut, and factories and construction sites were allowed to remain open only if the workers could sleep there.

President Museveni has addressed to the population eight times in the past few weeks, explaining his measures, encouraging the people and also praising them for their perseverence. The measures appear to have been successful in containing the disease, which so far has not been detected in any refugee camps or settlements in Uganda.

In Uganda, only 24% of the population is in employment, the remainder live hand-to-mouth making an income in the informal economy (street sales, market stalls, small shops, salons, sewing shops, car repairs, etc.) which is now completely closed. So the consequences of the Covid-19 measures are immense. People are hungry as they cannot work to earn money for food.

The lockdown has also affected the work of JRS Uganda, in the capital Kampala and in Adjumani, close to the South Sudan border.

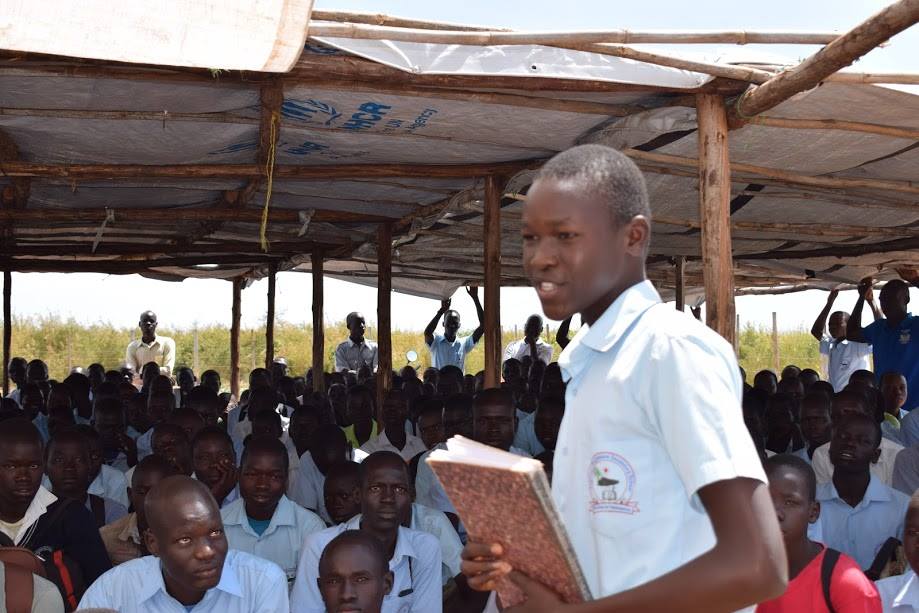

In Adjumani, the JRS team responded to the restrictions by planning radio lessons for primary and secondary school students as well as programmes to inform and educate the communities about the risks of Covid-19 and the measures needed to prevent it. Radio broadcasts will also contain information about the other dangerous diseases that the community is at risk from including ebola, cholera, yellow fever, malaria, AIDS, and measles, which have been in the background because of Covid-19.

Adjumani is home to refugee settlements which are home to many thousands of people from neighbouring South Sudan. The JRS team will also equip the settlements (e.g. marketplaces) and some schools in Adjumani with water tanks and hand-washing facilities. The Covid-19 restrictions have closed the borders for now, which means that hardly any new refugees have arrived in the country (which already hosts more than 1.4 million). But JRS expects a large number of new arrivals from South Sudan, Congo (DRC) and Burundi when the border reopens as conditions in these countries have not improved.

In Kampala, where JRS runs a training and education centre for urban refugees, the plan is to use the skills of the trainees to produce face masks, which are required at the moment and will be needed in the foreseeable future. As lockdown will continue for at least another week, it is unclear when the wEnglish and vocational training courses as well as kindergarten will resume. The team in the capital anticipates that the inability to earn over the past weeks will mean many people coming to the centre looking for food once restrictions are lifted.

In Uganda, there is no no unemployment benefit, only a few people have health insurance, and there are only 12 intensive care beds in the country. In the slum areas and sometimes also in the refugee settlements, people live closely together, and social distancing is hardly possible. The consequences of a Covid-19 epidemic in the country would be severe; but so too are the preventive measures.

With thanks to Frido Pflueger SJ, JRS Uganda.